We value your privacy

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

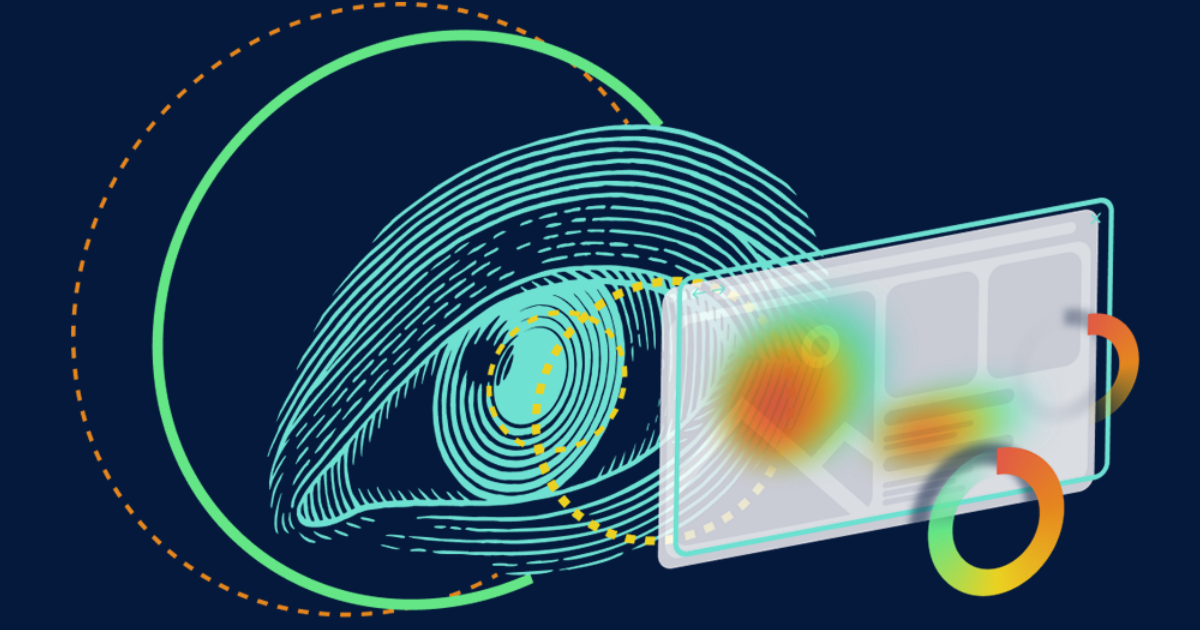

EyeQuant’s unparalleled visual analysis tool is the result of over 20 years of academic research by three of the world’s leading neuroscientists. We spoke with one of our co-founders, Peter König, to learn more about the history and heritage of the company and the research that forms its foundation.

During the conversation, we learned about Peter’s academic background and how he came to research cognitive science. We discussed the collaborative work that led to creating a company, and we got a glimpse into his vision for the future of AI-based visual analysis.

Initially studying physics, Peter developed a keen interest in complex systems. When thinking about which complex systems to study next, he was ultimately drawn to the “most amazing complex system of them all” – the human being – and took up medicine.

After completing his medicine and physics studies, the inevitable next step – and the subject of his new-found interest – was the human brain. It was the field of neuroscience that took him to academic projects in Frankfurt, San Diego, Zürich, and ultimately to the Institute of Cognitive Science in Osnabrück.

As it turned out, his previous studies of medicine and physics formed a very strong foundation for studying cognitive science.

“In medicine, you are focused on the human. In physics, you simplify things so much that you can understand the system, or how things work. The challenge was to learn how to simplify things enough to effectively apply quantitative methods, while also being able to make useful statements about humans.”

“This was a dynamic I enjoyed from the beginning, and a space in which I feel at home – trying to understand the human mind and human behaviour.”

While scientists have been studying eye movement for well over 100 years, the bulk of that research, especially in the first 60-70 years, was focused on the mechanics and low-level control of eye movement.

“For a long time, we had a very primitive understanding of eye movement – that was that we perceive, we decide, then we act. The most common example of this is in robotics: you use a camera to detect an object, and based on what it sees, you decide which action to take, then execute the action. I don’t believe that humans act that way – I am more a believer in embodied cognition.”

“As many philosophers have put forward, I believe our actions also define our perception. To take a very straightforward example, if you look at an object, then move your head back and forth, your view changes. As you experience that change more often and begin to understand or expect it, your movement begins to determine the quality of your perception.”

“This concept, and the relationship between movement and perception, was the catalyst to really delve into the study of eye movement and the relationship between action and sensation.”

“Eye movements are the most common action that people do. We make more eye movements than heartbeats, more than anything else. Nowhere else is the change of sensory signal so directly coupled with our actions, which made it a fantastic paradigm to investigate the simulation of sensation.”

Together with his peers and students, Peter bought eye trackers, created models and began trying to understand how, when, where and why we move our eyes. This led him to explore the concept of salience, where he teamed up with Christof Koch and Laurent Itti, who had already been doing research in this field.

At the time, Koch and Itti were already well on the way to becoming the leading neuroscientists they are now. Fast forward to today, and Christoph Koch heads up the Allen Institute and has an h-index of 162 – an impressive academic achievement by any standards. Notably, his review on saliency is his most cited paper.

Some of the earliest breakthroughs in his research were spurred on by the work of Peter’s innovative students at the Institute of Cognitive Science in Osnabrück. Peter and his team were able to simplify much of the data they had been working with by creating little building blocks – much like Lego – which could then be used in a graphics program to draw one’s own models.

By taking away all of the complexities of the mathematics and creating a simple model with building blocks, they were able to significantly scale up their testing and experimentation. It was also those very building blocks that led Peter to see a much broader use for this research, and the idea to start a company was born.

As Peter and his team began to understand more and more about eye movement and how our perception influences our behaviour, he found a growing challenge in trying to make this information useful for his new company’s customers.

While the customers were broadly interested in the research, ultimately, they wanted help solving their own problems.

For example, the first problem that the research could solve was that of salience – what people were focusing on. When you had an object within a scene that was viewed by, for example, 50 people for 10 seconds, the data model could – with rather precise accuracy – tell you how many times that object would be focused on.

This, however, was only the beginning. While the first question was reasonably easy to solve, it posed more, and increasingly complex questions. If there are multiple objects, which one is viewed first? How does this vary for different demographics with different perception norms?

It was possible to estimate an answer to these questions, but the science in doing so became markedly more complex. Further, while there are minor biases based on, for example, someone’s reading direction and language, or viewing behaviour evident in certain age groups, the overall impact on the application of the data is minimal.

Arguably as big a challenge as finding the answers was finding a way to visualise them and to communicate them to the customers.

“Yes, they wanted to know how we get to our conclusions, but ultimately, they just wanted to know whether they should make an item red or green!”

Since that time, there has been a concerted effort to improve the visualisation of eye movement analysis and the vast repositories of data that Peter and his team have amassed.

With the arrival and subsequent proliferation of AI, it has become increasingly possible to leverage eye-tracking data to create more meaningful visualisations, and at much greater speed.

As Peter explains, there is plenty of modelling work that can be carried out but the strength of biological data is that it endures over a much greater period of time as opposed to technology which evolves continuously.

“Much of people’s behaviour is habitual, not necessarily a result of a biological necessity. For example, we are used to seeing a logo in the upper-left corner of a screen, so naturally, this area draws our focus. These habits are historically constant, and slow to change.

“The greater opportunity is exploring emerging AI tools and technology to go from merely interpreting visuals, to creating even more intuitive, predictive tools. With the help of things like conversational AI, this is becoming much less the realm of imagination, and much more of a reality.”

Peter König:

For more on Peter König’s work please find a list of academic papers and cited papers (Cognitive Science, Cognitive Psychology, Neuroscience) here: https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?hl=en&user=Ieubd0EAAAAJ

Christof Koch:

For more of Christof Koch’s work please find a list of academic papers and cited papers here: https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?hl=en&user=JYt9T_sAAAAJ

Laurent Itti:

For more of Laurent Itti’s work please find a list of academic paper and cited papers here: http://iLab.usc.edu/publications/